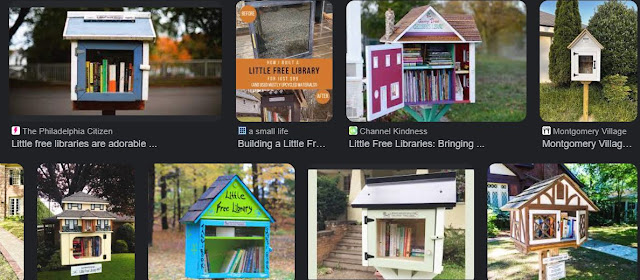

This was not a new encounter in that I had heard of them, but I had never gone to one before. Little Free Libraries was an initiative of a Wisconsin man, Todd Bol, who in 2009 made a model of a small schoolhouse (his mother had been a teacher), put books in it, and put it in his yard. In conjunction with Rick Brooks of University of Wisconsin-Madison, he saw the possibilities of the little libraries for encouraging social and community networks.

Inspired by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie’s mission during the early twentieth century to provide over 2,000 free libraries across the world, Bol and Brooks set a goal of matching Carnegie’s libraries by 2013. They reached their goal (2,508 little free libraries) in August 2012. The point of the libraries is to act as a focal point for communities. Books are donated, people borrow them, to return them later or pass them on to someone else. There are over 150,000 registered libraries in over 120 countries globally.

One of them is in the village here, set up during the pandemic. I had seen it, but not used it. Last Sunday, there a cake sale held in the village to raise funds for the refurbishment of the community hall; not only a good cause, but the cakes are always particularly lovely, and it has the distinction of being the only event here that ever starts on time. We dropped into the shop/post-office before heading home, and I took the opportunity to have a look in the library, and came away with a hard-copy of The Master and Margarita (M. Bulgakov, trans. Peavar and Volokhonsky). Like Arnie, I'll be back.

A new word during the week: sotoeis. An archaic word, found in one text only, the now fragmentary Book of the Copper Yew (Lebar an Buí-Eo). The manuscript itself is a strange compendium of historical fact (including an account of the anchorite Benjamin Bulbanus building a small curragh on Lough Derravaragh); paradoxographical tales (including the end of an account of a visit to the Isle of Apples, in which the narrator returns home by falling over a threshold, ‘thit mé thar an tairseach); and folklore (such as the tale of the Running Man of Lough Farderg).

The word sotoeis seems to be a verb, meaning to spoil a child or a pup, to teach bad manners through lack of discipline, to raise a sotaire, an upstart, or brat. Some scholars (Porphyrogenitus, Brother Barnabas, and others) argue that this interpretation is entirely wrong, and put forward the claim that sotoeis is related to the English word, soterial (in theology, meaning relating to salvation). The word occurs just once in this text, and neither definition makes much sense in its context, which is a story about a cow, a map, and the Queen of Sheba.

Oh, alright. I made it all up. 'Sotoeis' should have been ‘stories’, but I was typing my article too fast, and too inexpertly. But it looked like it should mean something…

And it did lead to two new (real) words of the week: soterial, and sotaire.

I have mentioned before the fact that place names around Ireland are intriguing because they are often neither in Irish nor in English, and require translation before the meaning of the anglicised Gaelic terms can be understood. Not so the Luas line towards Tallaght, whither I was bound on Tuesday, on which I was struck by the number of places with colours in their names: Blackhorse, Red Cow, Bluebell, and Goldenbridge. All in a row, they sound practically mythical.

Belatedly reading a February 16th tweet from John Coulthart in which he has received copies of Phosphor, a publication of the Leeds Surrealist Group, one of which contains an interview with the Czech surrealist film-maker and artist, Jan Švankmajer.

There were a number of comments on Coulthart's blog-post, mostly about Prague, but one offering as a lure to visit Kutná Hora the fact that there is an exhibition of the work of both Jan Švankmajer and Ewa Švankmajerová, to celebrate the former’s 90th birthday. The exhibition started on 2nd March and goes on until the beginning of August, so if I win the lottery in the meantime, there’s a destination, ready and waiting.

I visited Prague many years ago—Quettopolis in Hollowmen is partly based on it—and one of my favourite memories of it is of the puppet-performance of Monteverdi’s Orfeo, with the most gloriously mischievous serpent.

Last, but very far from least, it is International Women’s Day today. One of the reasons I am drawn to speculative fiction is that it does not take the world as presented to us as reflecting the full extent of its reality or potential. Layers of conventional expectations and conditioning distort or obscure our vision of what is and what might be: speculative approaches question and undermine these carefully constructed consensus ‘realities’.

Science fiction is often particularly effective, as it can show a different acceptance of ‘the way things are’ across time and space, taking completely for granted what would appear utopian or polemical in a contemporary setting. So Star Trek, in the 1960s, showed a black woman officer on the command deck of a military vessel as something utterly normal—placing the onus on those who resist this depiction to come up with cogent reasons (spoiler alert: there are none) why this could never be.

And just so the giants of the SF screen don’t hog all the limelight, I will list ten women authors whose work I particularly admire and/or enjoy. After all, in my life so far, I have been called upon more often to wield a pen or a word-processor than a phaser (though hope springs eternal, and all that). Some of these writers, like Agatha Christie, have been my companions since childhood; others, such as Olga Tokarczuk, are more recent acquaintances.

No comments:

Post a Comment